Joint letter – ICC reform and expansion risks diverting ETS Revenues from real climate action

In light of the European Commission’s ongoing considerations to amend the ETS State Aid Guidelines, revising the rules for Indirec...

News

Publish date: March 8, 2015

News

CAT POINT, Florida – It’s almost five years after the Deepwater Horizon blowout and Bellona’s Karl Kristensen and I have just struck oil on a beach in Cat Point, Florida – a state whose post-spill wounds have gone untreated for too long.

Guided here by Tampa area nurse and biologist Trisha Springstead – who is a one-person clearinghouse for the impact Florida sustained from the spill – we’ve shoveled through about 50 centimeters of freshly laid sand to discover a black, flaky layer of what Kristensen says is oxydized oil consistent with what poured out of BP’s Macondo well off the west coast of Louisiana.

“There’s a very distinct change in color about a half a meter down,” says Kristensen. “It looks to be oil contaminated sand and it ends very abruptly, so from the depth of where the layers are located, it fits well with the assumption that it was washed ashore a few years ago and then sedimented in the surface layer.”

We found it in three spots and charted a tar mass running along the tide line exactly where Springstead found it at a far shallower depth two years before.

A nurse of 40 years standing, Springstead made her original 5-hour trip north from her home near Tampa to Apalachicola on the Florida Panhandle’s aptly-named “Forgotten Coast” in 2011 when reports emerged that children were getting sick on the beach where we stand.

The symptoms of the three children she examined were identical to those thousands of BP spill cleanup workers have shown since the spill’s first days: rashes, respiratory difficulties, cardiac problems, declining mental acuity, diminishing memory, anxiety, a brownish discharge from their ears.

Two of the three children developed pneumonia in the heat of the summer. All this after a month of playing on the beach two years after the BP spill, Springstead told me.

A December study of weathered oil along Florida’s Panhandle by the BP-funded Gulf Of Mexico Restoration Initiative (GoMRI) attempts to obscure its connection to the 87-day oil gusher that began on April 20, 2010, when the BP-operated Deepwater Horizon rig exploded, unleashing 4.9 million barrels of oil in to Gulf waters and killing 11 men. The study won’t hazard a guess about the Florida oil’s toxicity, but says that such beaches can’t be considered “clean.”

Recalcitrant and weathered oil can become more toxic

Dr. Samantha Joye of the Department of Marine Resources at the University of Georgia – and the highest-profile scientific voice on the spill – told me by phone that she couldn’t judge the specific toxicity of the oil at Cat Point without analyzing it. But she said layers of weathered oil on beaches throughout the Gulf are not at all rare since the BP blowout – and they should be handled with extreme care.

In the case of the oil we dug up, there are many factors that could influence how toxic it is. Oil exposed to oxygen will biodegrade faster than oil the air can’t get to. Yet weathered oil, because it’s so resistant to biodegrading, can often gain in toxicity over time as the structure of the compounds it contains change.

“When you expose even highly reactive oil to photochemical weathering on the surface or biological weathering for even brief periods of time, the residual material you get is highly altered and not nearly as biodegradable as the starting material,” Dr. Joye told me.

As the children Springstead examined were sick, and because she herself broke out in a rash after visiting the beach that was consistent with those cleanup workers experience, it’s a safe bet the Cat Point oil was at least at one point toxic beyond usually expected levels.

Likewise, because the oil we found was not tar balls, we can assume it’s highly mobile.

“Hydrocarbons don’t tend to get stuck in one position,” Dr. Joye said. “They mobilize with what they’re associated with [and] beach sand is traveling constantly in the gulf.”

There’s a big chance that oil found even a half meter deep could wash back into the water column of the Gulf through storms or ground waters that might be flowing through the beach.

Springstead has arranged for an independent lab to sample the oil we found at Cat Point.

Ashley Williams, Gulf Coast Public Affairs Manager with the Florida Department of Environmental Protection told me by email and in phone conversations that she was unaware if there’d been reports of oil products on Cat Point.

From 2010 to June 1, 2013, she said, the US Coast Guard oversaw BP’s efforts to guard Florida’s beaches from oil, with assistance from the DEP. From then until December 31, 2014, the DEP continued monitoring Florida’s beaches. Since then, though, beach monitoring activities continue only on a volunteer basis.

She told me this doesn’t mean there aren’t more oily BP relics to be found in Florida.

“I wouldn’t say the beaches are totally clean,” Williams told me. “There’s definitely still oil there, and there will be for some time.”

Tracing Florida’s oil to the source

The summary of the GoMRI funded research indicated that the chemicals that weather oil cannot be readily determined. There are various assertions aloft that the oil found on the Panhandle is difficult to trace to the spill.

In 2012 Springstead reported her oil discovery to Dr Edwin Cake of Mississippi’s Gulf Environmental Associates, who is listed as a member of the Louisiana Department of Natural Resources’ Oyster Lease Damage Evaluation Board.

Cake suggested in an email Springstead showed me that the Cat Point oil could have come from a tugboat or barge beaching during a 2000 construction project in the area.

But the trail of breadcrumbs tying the oil to the Macondo well is far too compelling.

Ben Sherman, the national communications director for National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), emailed me links to BP spill maps showing Cat Point and surrounding areas were hit.

The Florida DEP’s Williams emailed me figures showing that cleanup teams had picked up 60,000 tar balls and a total of 1838 kilograms (4050 pounds) of Macondo well origin oil products on Panhandle beaches alone over the last year and a half.

Then there’s the issue of our oil’s apparent resistance to biodegradation. It’s been in the same spot for at least two years. Joye said that the residual oil left in the Gulf system as a whole may be resistant to biodegradradation.

Out of season Corexit campaign

Then there are local witness reports of extensive spill response operations that ramped up off the Florida coast, the bulk of which they say began closer to 2011.

These witnesses, who are fishermen, coastal residents, business owners and activists, told me the US Coast Guard sprayed waters from the Panhandle as far south as Tampa for more than a year after the dispersant sorties officially stopped on July 19, 2010.

Petty Officer Seth Johnson of the US Coast Guard communications team in New Orleans didn’t outright deny the witness reports in a telephone interview with me, but said any Corexit dump beyond the July date “wasn’t part of the official Deepwater Horizon response.”

The record of the acknowledged official response, Johnson said, is contained on the sprawling NOAA-run online Environmental Response Management Application, which he told me “reportedly” contains flight records of each Corexit sortie, as well as locations and volumes of the sprays.

But even a week after my initial email inquiry, Johnson said he and his colleagues had been unable to locate information pertaining to potential 2011 sprays on the website.

“We’ve got someone looking through the ERMA site to find that information, but there’s so much information it’s mindboggling,” he said.

Johnson’s right. I didn’t have any better luck at finding complete records for individual flights. But one section of the website, called Aerial Dispersant Applications, lists daily summaries of sorties from April 22, 2010 – two days after the blowout – through the official close-down date.

Even these, however, say that, “original flight data has been merged to create a single daily composite of all dispersant flights.” Digging deeper into the metadata finally reveals coordinates of where sprays took place. But there is little other information that can be readily accessed or processed by the lay public.

Florida reports show continued oiling

Local science shows that BP oil products are still hitting Florida five years on. A study published late last month by the University of Southern Florida said dissolved Deepwater Horizon oil wafted underwater as far south as Sanibel Island, causing fish illnesses along the way.

Robert Naman, a chemist at Mobile, Alabama’s Analytical Chemical Testing Lab, told me he thinks a lot of oil is still sweeping up from the bottom of the 1000-meter deep De Soto Canyon, 100 kilometers southwest of Panama City, Florida. This area used to represents some of the nation’s most fertile fishing territory, but is now, according to local fisherman and Naman, a dead zone.

Naman has studied oil’s reaction to dispersant and estimates that the bottom of the 350-kilometer long canyon has been covered by some 100 to 300 meters of BP crude and Corexit.

Oil parked on Florida’s shelf

University of Southern Florida oceanographer Bob Weisberg is the co-author on the study that jibes with Naman’s theory.

Weisburg reported that a major upwelling — meaning a swirling current of cool water from deep in the gulf — started in May 2010, a little less than a month after the spill, and continued through the rest of that year.

The upwelling, said Weisburg, could have snagged underwater plumes of dispersed oil off Florida’s Panhandle, plumes that were discussed in a paper by David Hollander of University of South Florida.

The upwelling then pushed the plumes southward onto the shelf off Florida’s west coast, Weisburg told the Tampa Bay Times.

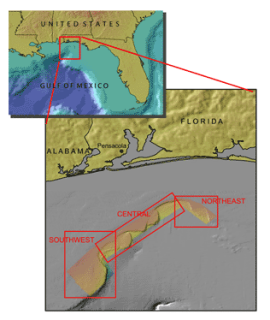

Plumes appeared in various places, and were initially discovered by Joye in the Southwest quadrant of the Gulf.

Fish harvests lack a pulse

Florida fishermen, meanwhile, are barely scraping by since 2011. Oysters and clam harvest are at a standstill. Everything fishermen pull up is dead. Those that do turn up oysters find they are too pocked with unidentified growths to bring to market.

Some fishermen who refuse to do so often find themselves forced by large fisheries to sell products they know to be toxic, many of them told me on the request I not name them in print for fear of retaliation.

And oil is still charging the beaches: On March 2, a field trip of high school students spent the day at a beach near Pensacola picking up tar balls.

Tar balls as bacterial killers?

Tar balls are magnets for bacteria. One of these is Vibrio Vulnificus, which can cause dire lesions that appear to eat skin, and can have a mortality rate of 45-50 percent if poorly treated. Vibrio Vulnificus is a common bacteria found in Gulf coast waters, including fresh water estuaries, and can be spread through a variety of means, such as cutting one’s skin on clam shells or eating undercooked shellfish.

But in the summer of 2014, 41 people in Florida presented with symptoms of Vibrio Vulnificus exposure, and three of them died, local and national media reported. Covadonga Arias, a professor of microbial genomics at Auburn University in Alabama, found that Vibrio Vulnificus was 10 times higher in tar balls than in sand, and up to 10 times higher than in seawater.

Children and the elderly are especially vulnerable to Vibrio infections. During last summer’s outbreak, health officials spurred by Arias implored beach goers to steer clear of tar balls.

A NOAA report on tar balls and Vibrio Vulnificus from last summer read, ”It is not surprising to find high levels of bacteria associated with these oil sources [tar balls], although why V. vulnificus is present at such high levels is an intriguing question […] The implications to public health also remain unclear,” as quoted by the Houston Chronicle.

Florida’s message to the oiled ill: Shut up

But perhaps the most acute and neglected connection between the Florida experience and the BP blowout is state’s heightened incidence of spill related illnesses.

The Florida medical community brushes the conditions – which are well publicized in other Gulf states – under the rug. People are frustrated, getting sicker, and want action. But outspokenness in these small, economically deprived communities is discouraged, and those doing the discouraging have a lot of leverage: intimidation, surveillance, financial ruin and physical threats.

All but one of the witnesses who spoke to me requested anonymity for fear of violent reprisals. They reported tinkering with their vehicles, job losses, bullet holes getting blasted in their boat hulls, mysterious car tails, and suspicious accidental deaths.

The Florida Department of Health, when contacted by telephone, could provide no information on how many, or even whether, it had received any reports on patient presenting with spill related symptoms. This contrasts sharply with health departments in other Gulf states. Louisiana’s has even provided for spill victims who can’t work to collect state assistance.

Why is Florida the spill’s ‘red headed step-child?’

Chemist Naman, said that Florida has a big strike against having its woes aired to an international audience: The state draws $67 billion annually in tourist revenue, and its most acute oil spill problems didn’t emerge until long after the news cycle had moved on to other things.

“Florida, because it’s so far east of ground zero, is behind the eight ball in national attention,” Naman said. “The chemicals and crude as they come across the Gulf also mutate in ways that the NOAA and [Environmental Protection Agency] were slow to put their finger on, so it’s been easier to ignore us.”

Charlie Christ, who was Florida’s governor at the time of the spill, didn’t do much to appropriate funds to defend the state against the coming slick. Instead, he got $35 million from BP to spend on a huge advertising campaign to boost tourism in the heat of the spill, the Palm Beach Post and numerous other Florida media reported.

The TV blitz that began in May 2010 featured stock images of happy beachgoers and repeated phrases like “the coast is clear” and “Northwest Florida is open for business.” Many, said Springstead, believed the ads, only to return home with spill related illnesses.

But sick Floridians remained the most overshadowed, both in the wake of the ads and the heavy focus on Louisiana.

“All the folks over in Louisiana, they got oiled everywhere and had so many problems that we weren’t taken into consideration by comparison,” Peter Frizzell, 60, a retired musician and citizen-expert on the BP disaster from Cedar Key, Florida told me. “So we, over here in Florida, were kind of the red-headed step children of the spill.”

Medical nightmares for Springstead started on the the ‘Forgotten Coast’

Before and since Springstead’s original trip to Cat Point, she has collected medical records dating back to 2011 that indicate more than 350 Floridians are suffering with ailments associated with exposure to oil and Corexit.

But, she says hundreds more cases have been misdiagnosed by ER doctors unable to connect the dots. Still more would-be patients don’t seek care because they’re too poor to afford medical insurance. Yet others are simply too scared to make waves.

One product of a baffled medical community is Frizzell himself, who spent months shuttling his bleeding lungs to Shands Hospital at the University of Florida, 60 kilometers from his home. Frizzell was hit head on by a Corexit dump from what he identified as a C-130 military aircraft in March 2011 while kayaking off Cedar Key – nine months after the dispersant drops were to have stopped. The University of Florida received millions in research grants from BP.

Frizzell turned to the university’s hospital ER when he started coughing up blood. The doctors turned up nothing and said he was “okay.”

“When they said that, I held up my hand and coughed a bunch of blood onto it and held it out to them,” said Frizzell. “And I asked, ‘does that look okay?’”

‘Son, your lungs blew up’

During further ER visits, Frizzell’s physicians pursued a cancer diagnosis. Several MRIs, which didn’t corroborate that, depleted his savings and landed him on charity healthcare.

An eventual examination of his bronchial tubes revealed shocking irritation.

“The doctor got right to the top of my bronchial tube and could see blood boiling,” Frizzell told me. “He told me he had never seen anything like this and thought it was a heavy infection and put me on an antibiotic.”

Frizzell was scheduled for yet another MRI and returned to the ER some weeks later to undergo the scan. While waiting, one of the hospital staff who helped him manage his charity care approached him with an October 2010 article published by Al Jazeera – the first to break the connection between Corexit use and myriad life-threatening health issues along the Gulf after the blowout.

“[The staff member] looked at me and said, ‘you were exposed to this stuff,” said Frizzell. One of the article’s sources was Springstead, and she and Frizzell eventually met and got him a medical opinion that connected his symptoms to the spill.

The new doctor looked at Frizzell’s MRIs and said “’son, your lungs blew up.’ More specifically, what he meant is that the red blood cells in my lungs had exploded,” Frizzell said.

This, say Springstead and Dr. Susan Shaw, a physician with the State University of New York at Albany, is a hallmark symptom of Corexit toxicity. Unfortunately, it’s only one of several dozen more that could begin to turn up.

For the moment, Frizzell’s counting himself lucky. He’s dug into research, and with Springstead, started publicly asking the questions local doctors won’t. Their inquiries have created a critical mass of other sufferers in Florida – and drawn significant intimidation along the way.

One of his friends, whose name he prefers not appear in print, died of cancer a mere 18 months after getting soaked in 2011 by another C-130 spaying Corexit over the same waters where Frizzell was hit.

Cancer is hardly uncommon among BP spill victims of late. Shanna Devine with the Government Accountability Project

told me in a January interview that Gulf communities were reporting even higher incidence of cancer to her group than was reported in August, when we originally talked about the subject.

Dr. Shaw and Dr Riki Ott, one of America’s most eminent marine biologists and oil spill experts, both told me in interviews that the medical community lacks a diagnostic criteria for dealing with such patients – and Ott said patients in the Gulf of Mexico are more likely to be neglected.

“There’s a direct correlation between someone’s zip code and their access to good health care,” she said. “The richer the zip code, the better the care – most southern zip codes where you find fishing communities don’t have the health facilities to cope with this.”

Dead calm

As Springstead, Kristensen and I leave the Apalachicola zip code, we pass abandoned, tumble down fisheries are in bad health too. We kick around some of the abandoned oyster processing facilities, which are so far out of commission they no longer even bear the stench of rotting seafood.

The expanses of water on either side of us are dead calm. No fishing boats, or any other boats for that matter, are in evidence anywhere.

More haunting is that there’s not a single seabird to be seen, not even seagulls with their dumpster raiding habits. It seems that whatever there would have been to eat has long departed.

Why, exactly, is not clear. The Gulf has been impacted by multiple stressors. Is it the oil, or is it the oil in combination with other anthropogenic impacts in combination with the oil?

According to the most reliable science on the issue, it will many years before we understand, as separating the symptoms of the oil spill from the Gulf’s other woes.

This is the first in a series of articles Bellona is producing for the fifth anniversary of the Deepwater Horizon spill.

In light of the European Commission’s ongoing considerations to amend the ETS State Aid Guidelines, revising the rules for Indirec...

Today, the European Commission adopted a new Union list of energy Projects of Common Interest (PCIs) and Projects of Mutual Interest (PMIs), granting...

Central and Eastern European economies that have historically relied heavily on energy-intensive industries now face challenges in modernising their ...

By Carbon Balance Initiative (CB), Clean Air Task Force (CATF) and Bellona Europa As reported by Euractiv, at least 15 oil and gas producers...

Three main asks: Establish a robust EU biomass hierarchy to ensure limited bioresources are directed to the highest climate value and...

Get our latest news